In New Orleans, Rust in the Wheels of Justice*

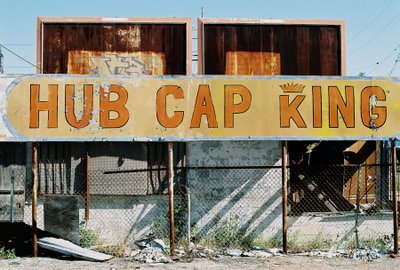

Hub Cap King, New Orleans 10/2006

Hub Cap King, New Orleans 10/2006all reproduction rights reserved William Greiner

In New Orleans, Rust in the Wheels of Justice

By CHRISTOPHER DREW

Published: November 21, 2006

The Times-Picayune New Orleans

NEW ORLEANS — Seventeen months ago, when Edward Augustine was arrested with what the police said were marijuana and crack cocaine in his pocket and a handgun in his waistband, he seemed like just another run-of-the-mill drug suspect: easy to prosecute, easy to lock up.

But two months later, the floodwaters rushed through the labyrinth of evidence rooms in the courthouse basement here, scattering tens of thousands of items and leaving a fetid mess. When Mr. Augustine finally came to trial in October, the authorities could no longer find the three things they needed most: the small bag of marijuana, the rocks of crack and the gun. The judge threw out the case, and Mr. Augustine walked free.

As the judge, Lynda Van Davis, put it, Mr. Augustine, 18, had lucked out. But he is not the only lucky defendant in New Orleans. As the city’s criminal justice system slowly gears back up after Hurricane Katrina, as many as 500 defendants, mostly in drug, theft and assault cases, have been freed because of problems with evidence, including difficulty in finding the witnesses who have moved away.

Law-enforcement officials say a few of those who were freed could potentially be violent, a cause for concern in a city battling a surge in drug-related killings. And some judges say that missing witnesses and damaged evidence, like spoiled DNA samples and rusted guns, will almost certainly lead to more acquittals, even in cases of murder, rape and armed robbery.

“It’s amazing that for every case I’ve walked into lately, there’s evidence missing,” said Rick Tessier, a defense lawyer.

Several judges have jettisoned cases like Mr. Augustine’s over the last few weeks. And in acquitting him, Judge Van Davis chastised prosecutors for going ahead without the drugs or the gun.

“This is ridiculous, absolutely ridiculous,” she said from the bench.

But the district attorney, Eddie Jordan, responded in an interview, “We can’t just tuck our tails between our legs and run just because it’s difficult.”

Mr. Jordan said that under state law, testimony from the arresting officer, and a laboratory report that confirmed Mr. Augustine had possessed illegal drugs, should have been enough to convict him. He added that although the evidence problems might seem to be “an Achilles’ heel,” he did not think “that the overwhelming problems that some of the critics have speculated about have materialized.”

While 800 suspects have pleaded guilty to various crimes since the New Orleans courts reopened in June, only about 90 trials have been held, about a third the normal number. More than 2,000 people arrested before Hurricane Katrina are still waiting for their cases to be heard, and at least 400 of them remain in jail. And 1,500 cases have been temporarily set aside because the defendants, who were out on bond, apparently evacuated and never returned.

Court officials say other delays have come from a shortage of jurors and from limits on how many inmates can be brought to court each day. And the public defender’s office is so overwhelmed that it is recruiting law students from across the country to conduct interviews with long-neglected clients who cannot afford a lawyer.

But a growing source of delays and acquittals has been the lack of witnesses and evidence.

After Hurricane Katrina hit in August 2005, the evidence rooms at the Orleans Parish Criminal District Court sat in chest-high water for two and a half weeks. Only recently have court officials begun to realize the extent of the evidence problems within the old Beaux-Arts courthouse, which was closed for nine months and is still not quite back to full operations.

Warren E. Spears, the clerk in charge of the evidence rooms, said in an interview that before the storm only about 10 percent of the hundreds of thousands of items had been sealed in plastic bags. The rest were in paper bags and scrap boxes holding clothes, guns and drugs, some of which disintegrated in the swirling waters, Mr. Spears said, dumping their contents into heaps on the floor.

Clothing from murder and assault cases took “a brutal beating,” Mr. Spears said. Photo lineup cards used to identify suspects stuck together and could not be separated. Stacks of assault weapons turned to rust, he said, and holes had to be punched in duffel bags filled with rotting marijuana to let the water out.

The court hired a cleanup contractor to gather the evidence, clean off the mold and place it in plastic bags and fresh boxes. Court officials have estimated that 8 percent to 10 percent of the evidence was a total loss.

Mr. Spears added that a number of the workers spoke little English, and that he could only gesture to them as they guessed which items should be packaged together.

Water also seeped into safes, he said, rotting a great deal of paper money that had to be freeze-dried to remove the moisture.

At separate police evidence rooms nearby, some DNA samples for rape and murder cases were held for months without refrigeration, possibly ruining their usefulness, other officials said.

Given shortages in staffing, the condition of the evidence comes to light only as each case approaches trial.

The problems are starting to make life easier for the city’s defense lawyers.

Pamela R. Metzger, a member of a state board that oversees the public defender’s office, said she had learned about the evidence problems after asking Mr. Spears about a suspected crack pipe that was missing in one of her cases. Ms. Metzger, who is also a law professor at Tulane University, said she was urging the public defense lawyers, who handle the vast majority of the court’s cases, to raise more challenges about the condition of the evidence and how it had been handled.

“I think you’ll see more and more and more of that,” she said.

Mr. Jordan, the district attorney, said his office had taken the lead in dismissing 400 to 500 cases recently, mainly because crucial witnesses, like the victims or the arresting officers, had moved away.

“Many of my prosecutors had held on to those cases until the last minute in hopes that we’d be able to go to trial,” he said. “But I thought that if we had not been able to contact the victim since before the storm, then it was unlikely we’d be able to reach them now.”

Mr. Jordan also said his office had won about 60 percent of the roughly 90 trials since the courts reopened. While several judges have been tough, others recently convicted suspects on cocaine and burglary charges even though the physical evidence had been lost, he said.

Of one recent jury case, he said: “We weren’t certain we had the same gun from the crime scene. But we were able to find a gun that fit the description. And we found a photo of the original gun, and the jury found the defendant guilty as charged.”

Still, Mr. Jordan said he had recently hired a former federal prosecutor to assess the strength of the 2,000 pre-hurricane cases to see how many more should be dropped.

Mr. Tessier, the private defense lawyer, said he had recently taken on a widely publicized murder case in which his client and another man were charged with stabbing a Tulane student in 2002.

The lawyer said the files had indicated that an important piece of evidence was a shirt stained with a drop of his client’s blood. But Mr. Tessier said that neither Mr. Spears nor the New Orleans Police Department, which is temporarily storing evidence in rental trucks, had been able to find the shirt.

Katherine Mattes, another Tulane law professor, said the lost or damaged evidence could also make it harder for innocent people to shake off charges filed against them. She said, for instance, that a rusted gun might no longer fire, making it impossible to conduct new ballistic tests that might show it could not have been used in a murder.

“What people say when you describe all the evidence problems is how terrible it will be if we have people who committed crimes and can’t be prosecuted,” she said. “But it also can work the other way.”

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home